Sting the Renaissance man...

Wealthy rock stars of a certain age sometimes need to find new hobbies to keep themselves amused. Ozzy Osbourne made a disastrous foray into quad-biking, but Sting's decision to indulge his fondness for the Elizabethan composer John Dowland is, typically, far better planned and executed.

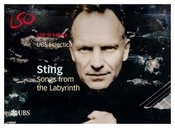

In the copious sleeve notes to 'Songs From The Labyrinth', his new CD of Dowland's music, Sting stresses that the project is the culmination of a 20-year ''haunting'' by the doleful lutenist, and he tries to bridge the 400-year culture gap by observing that Dowland might have been the original ''alienated singer songwriter'', although it surely sells the brilliant Dowland short to cast him as a kind of Elizabethan Nick Drake.

This performance (part of the UBS Eclectica series at St Luke's/and recorded for Radio 3) loosely followed the structure of the album, Sting interspersing the songs with extracts from a letter from Dowland to Sir Robert Cecil, Queen Elizabeth's chief of security, to provide insights into the composer's life and times.

Sting used to be a teacher and knows the value of preparation, but although he has been studying the lute, most of the accompaniment was from the Bosnian virtuoso Edin Karamazov.

Karamazov's playing was reliably superb, but there were passages where Sting was feeling his way.

Finding the appropriate vocal register seemed to cause him problems, for instance in 'Clear or Cloudy', where his pseudo-comic tone collapsed in a heap. The problem might be that the lute produces such a low volume of sound that the singer is left perilously exposed. especially if he's more accustomed to performing in arenas through millon-watt amplifiers. The deeper his voice dropped, the more it wandered away from the tune, or lapsed into curious ''waaaah'' noises. Sting was most convincing when he was able to use his familiar high; husky tone, as in 'Weep You No More, Sad Fountoins', where his sustained notes floated over Karamazov's' melancholic pluckings to haunting effect.

For a finale, Sting accelerated through the centuries with versions if his own songs 'Fields of Gold' and 'Message in a Bottle', provoking eager applause from an audience relived to find itself on familiar turf. Earlier he'd played 'Have You Seen The Bright Lily Grow?' by Robert Johnson, so he threw in 'Hellhound on my Trail', by bluesman Robert Johnson, as a jokey counterpoint. It sounded surprisingly good on the lute.

(c) The Daily Telegraph by Adam Sweeting

Lute sweet...

A slightly bemused Sting is doing an onstage pre-concert interview with Radio 3. For 20 years he has been haunted and humbled by the music of the great Elizabethan composer and lutenist John Dowland - 'the music of self-reflection,' he says, 'and melancholy, a much-neglected emotion nowadays'.

In collaboration with Bosnian lutenist Edin Karamazov, Sting has recorded an album of Dowland's feverish, lovelorn songs, after years of having friends (comedian John Bird, pianist Katia Labeque) tell him his voice would be perfectly suited to the task.

And there's a full church to witness the spectacle: tables and chairs close to the stage reserved for wife Trudie Styler and co; in the ordinary seats behind, the likes of Britain's leading tenor, Ian Bostridge. Sting, understandably, appears a little nervous. Hands on pinstriped thighs, white shirt unbuttoned to his chest hair, he is self-deprecating ('Dowland was born in 1563, which makes him only slightly older than me') and keen to present the evening as a celebration not of his own boundless eclecticism but of Dowland, 'the first alienated singer-songwriter'.

And then he melts into the dreamy 'Flow, My Tears', and there's real joy in his easy way with 'The Lowest Trees Have Tops' and its rapturous refrain: 'And love is love/ In beggars and in kings'. Karamazov accompanies with self-absorbed elan while Sting looks on in rueful admiration. When he finally picks up his own lute, a gift from another friend and 'unique', assorted expressions of sheer concentration flit across his face.

Prefiguring 'Every Little Thing She Does is Magic' by 400 years, there's a lovely 'Come Again' ('To see, to hear, to touch, to kiss, to die/ With thee again in sweetest sympathy') and, not long after, momentarily alone, Trudie is on her feet for a standing ovation.

(c) The Observer by Carol McDaid

Sting, LSO St Luke's, London...

Sting's latest artistic venture, despite being pregnant with pratfall potential, is a remarkable triumph. ''Haunted'' for 20 years by the maudlin music of the Elizabethan songwriter and lutenist John Dowland, Sting has recruited Bosnian lute maestro Edin Karamazov to record an album of Dowland's compositions, 'Songs From the Labyrinth'. The stage would appear to be set for an evening of over-reaching pretension.

The project is saved, however, by the affection both men clearly feel for their arcane subject. Dowland's music is marked by a doleful, spectral introspection, and Sting subjugates his rock-star ego before the spirit of the songs, filling in their outlines in his pitch-perfect and surprisingly resonant tenor.

Tunes such as 'Come Again', all febrile sprung rhythms and spindly-yet-sensual counterpoint, are plangent and intimately evocative. Sting gamely plucks his lute and Karamazov is a virtuoso, drawing profound joy and complex vibrations from his arsenal of instruments like a madrigally inclined Jimmy Page.

Famously a former teacher, Sting approaches the evening with a pedagogue's air, explaining the minutiae of Dowland's life, and reading excerpts from the composer's correspondence between songs. This attention to detail enhances the delicate delights of a gossamer ditty such as 'Have You Seen the Bright Lily Grow', written for the soundtrack of a play by Ben Jonson.

''I've played to some of the biggest audiences in history, over half-a-million people at a time,'' says Sting in closing, ''but I've never felt as nervous as I did tonight.'' Such trepidation was unnecessary: against all expectations, this was a genuine tour de force.

(c) The Guardian by Ian Gittins

Unplugged, he's no Renaissance man...

Ever since early music's Pied Piper David Munrow hit the small screen in the Seventies, the lute has steadily moved up the charts as the thinking man's guitar. And Sting is, by -rock standards, the quintessential thinking man: his route to the lute began 20 years ago when a friend propelled him towards Peter Pears and Julian Bream doing John Dowland.

At that time he couldn't see any mileage in it for himself, any more than he could when Katia Labeque suggested that Dowland's songs might suit his ''unschooled tenor'', but he was drawn ever deeper into what he calls the ''labyrinth''. Stuff kept happening: he was given a custom-built lute with a labyrinth-shaped rose-hole, and he stumbled into a collaboration with the Sarajevan lutenist Edin Karamazov.

And, after years of patient readjustment of brain and fingers to this guitar-which-is-not-a-guitar, Sting has now unveiled a CD entitled 'Songs from the Labyrinth', consisting of Dowland's loveliest works interspersed with lute fantasias and extracts from the composer's letters.

Which brings us to the LSO's beautifully converted Hawksmoor church, together with ticket touts, rock celebs, the early-music fraternity and Fiona Talkington, who explains that what we are about to hear will shortly reverberate round every corner of Radios 2 and 3. Taking the stage with Karamazov, Sting modestly remarks that he'll be singing in his own style, ''but one hopes in a respectful way''. And he has a pertinent thought to pass on: Dowland's, he says, is ''the music of self-reflection, which leads.to melancholy, which has nothing to do with depression, and is an undervalued emotion in modern times''. Well put.

Whereupon he launches into 'Flow My Tears'. Having listened to the CD, I've been looking forward to this moment: Sting has none of the preciousness one associates with amateur shots at Dowland, and his mildly transatlantic accent forces me to listen to the music as something entirely new. But what a shock when he opens his mouth: shorn of that studio mastering, which turns recorded dross into gold, his sound is awful, by turns a croon and a rasp. And he's trying so hard, in all the wrong ways, that it positively hurts to listen.

For this church has an unforgivingly faithful acoustic, and Dowland's melodic lines have the beauty of simplicity: Sting is stripped naked. In one pre-concert interview he argued that since this music pre-dated opera, his lack of ''technique'' didn't matter. That may be true, but we're here about something more universal than mere bel canto - about an artistry that spans everything from Big Bill Broonzy to superstar tenor Ian Bostridge, who just happens to be sitting in my row. And poor old Sting, for all his good intentions, simply hasn't got it. It's worst when he attacks one of Dowland's longheld high notes, but it's pretty bad throughout. The only time it becomes bearable is when he roughens up the street-cry in 'Fine Knacks for Ladies', or hardens his tone against his moody mistress in 'Clear or Cloudy'. I begin to long for Bostridge - or any decent folk singer - to replace him, and demonstrate what good singing is.

The concert doesn't last long -just the length of the CD - but when the celebs have given him their ritual ovation he picks up his lute, turns it into a guitar, and launches-into one of his own songs - and we realise that he can sing after all. Performing for 5,000 people is a breeze compared with this, he explains: ''I was never so nervous in my life.'' Now he, his instrument, and his material are one, and we all breathe a collective sigh of relief: don't give up your day job.

(c) The Independent by Michael Church

Sting at LSO St Luke's, EC1...

Ever the Renaissance man, Sting has lately turned his attention to playing the lute, devoting himself for the best part of two years to an intense study of the 16th-century composer and performer John Dowland. The fruits of this “labour of curiosity” can be heard on a new CD, 'Songs from the Labyrinth', a collection of music and readings from the letters of Dowland, performed by Sting and the lutenist Edin Karamazov, which was brought to life at a recital in the restored St Luke’s.

It quickly became clear that Karamazov was going to be shouldering the lion’s share of the actual lute playing. His fingers flew in acrobatic combinations across the giant fretboard, while Sting, sitting bolt upright, broached the dolorous lyric of 'Flow my Tears'. “Let me mourn/ Where night’s black bird her sad infamy sins/ There let me live forlorn,” he sang. The lute sounded glorious - like a classical guitar but fuller and more ripened. And Sting sounded... well, like Sting.

And here was the curious thing. Glib and pretentious as the whole exercise might appear on the surface, there was a clearly discernible link between the millionaire pop star of the 21st century and the wandering minstrel of yore. In technical terms, Sting couldn’t hold a candle to any one of the singers from the vocal group Stile Antico, who joined the duo for a swirling rendition of 'Can She Excuse My Wrongs'. And his lute playing would probably not have earned him a position in the courts of medieval Europe. But the harmonic intervals in Dowland’s airs and the general thrust of a song such as 'The Lowest Trees Have Tops' did not sound that far removed from the music that Sting is known for.

As if to underline the point a mischievous choice of encores included Sting’s own song 'Fields of Gold', a Robert Johnson blues, 'Hellhound on my Trail' and the Police hit 'Message in a Bottle', all rendered in the courtly, lutenist style. Dowland may have been spinning in his grave, but it was surprisingly good fun.

(c) The Times by David Sinclair

Wealthy rock stars of a certain age sometimes need to find new hobbies to keep themselves amused. Ozzy Osbourne made a disastrous foray into quad-biking, but Sting's decision to indulge his fondness for the Elizabethan composer John Dowland is, typically, far better planned and executed.

In the copious sleeve notes to 'Songs From The Labyrinth', his new CD of Dowland's music, Sting stresses that the project is the culmination of a 20-year ''haunting'' by the doleful lutenist, and he tries to bridge the 400-year culture gap by observing that Dowland might have been the original ''alienated singer songwriter'', although it surely sells the brilliant Dowland short to cast him as a kind of Elizabethan Nick Drake.

This performance (part of the UBS Eclectica series at St Luke's/and recorded for Radio 3) loosely followed the structure of the album, Sting interspersing the songs with extracts from a letter from Dowland to Sir Robert Cecil, Queen Elizabeth's chief of security, to provide insights into the composer's life and times.

Sting used to be a teacher and knows the value of preparation, but although he has been studying the lute, most of the accompaniment was from the Bosnian virtuoso Edin Karamazov.

Karamazov's playing was reliably superb, but there were passages where Sting was feeling his way.

Finding the appropriate vocal register seemed to cause him problems, for instance in 'Clear or Cloudy', where his pseudo-comic tone collapsed in a heap. The problem might be that the lute produces such a low volume of sound that the singer is left perilously exposed. especially if he's more accustomed to performing in arenas through millon-watt amplifiers. The deeper his voice dropped, the more it wandered away from the tune, or lapsed into curious ''waaaah'' noises. Sting was most convincing when he was able to use his familiar high; husky tone, as in 'Weep You No More, Sad Fountoins', where his sustained notes floated over Karamazov's' melancholic pluckings to haunting effect.

For a finale, Sting accelerated through the centuries with versions if his own songs 'Fields of Gold' and 'Message in a Bottle', provoking eager applause from an audience relived to find itself on familiar turf. Earlier he'd played 'Have You Seen The Bright Lily Grow?' by Robert Johnson, so he threw in 'Hellhound on my Trail', by bluesman Robert Johnson, as a jokey counterpoint. It sounded surprisingly good on the lute.

(c) The Daily Telegraph by Adam Sweeting

Lute sweet...

A slightly bemused Sting is doing an onstage pre-concert interview with Radio 3. For 20 years he has been haunted and humbled by the music of the great Elizabethan composer and lutenist John Dowland - 'the music of self-reflection,' he says, 'and melancholy, a much-neglected emotion nowadays'.

In collaboration with Bosnian lutenist Edin Karamazov, Sting has recorded an album of Dowland's feverish, lovelorn songs, after years of having friends (comedian John Bird, pianist Katia Labeque) tell him his voice would be perfectly suited to the task.

And there's a full church to witness the spectacle: tables and chairs close to the stage reserved for wife Trudie Styler and co; in the ordinary seats behind, the likes of Britain's leading tenor, Ian Bostridge. Sting, understandably, appears a little nervous. Hands on pinstriped thighs, white shirt unbuttoned to his chest hair, he is self-deprecating ('Dowland was born in 1563, which makes him only slightly older than me') and keen to present the evening as a celebration not of his own boundless eclecticism but of Dowland, 'the first alienated singer-songwriter'.

And then he melts into the dreamy 'Flow, My Tears', and there's real joy in his easy way with 'The Lowest Trees Have Tops' and its rapturous refrain: 'And love is love/ In beggars and in kings'. Karamazov accompanies with self-absorbed elan while Sting looks on in rueful admiration. When he finally picks up his own lute, a gift from another friend and 'unique', assorted expressions of sheer concentration flit across his face.

Prefiguring 'Every Little Thing She Does is Magic' by 400 years, there's a lovely 'Come Again' ('To see, to hear, to touch, to kiss, to die/ With thee again in sweetest sympathy') and, not long after, momentarily alone, Trudie is on her feet for a standing ovation.

(c) The Observer by Carol McDaid

Sting, LSO St Luke's, London...

Sting's latest artistic venture, despite being pregnant with pratfall potential, is a remarkable triumph. ''Haunted'' for 20 years by the maudlin music of the Elizabethan songwriter and lutenist John Dowland, Sting has recruited Bosnian lute maestro Edin Karamazov to record an album of Dowland's compositions, 'Songs From the Labyrinth'. The stage would appear to be set for an evening of over-reaching pretension.

The project is saved, however, by the affection both men clearly feel for their arcane subject. Dowland's music is marked by a doleful, spectral introspection, and Sting subjugates his rock-star ego before the spirit of the songs, filling in their outlines in his pitch-perfect and surprisingly resonant tenor.

Tunes such as 'Come Again', all febrile sprung rhythms and spindly-yet-sensual counterpoint, are plangent and intimately evocative. Sting gamely plucks his lute and Karamazov is a virtuoso, drawing profound joy and complex vibrations from his arsenal of instruments like a madrigally inclined Jimmy Page.

Famously a former teacher, Sting approaches the evening with a pedagogue's air, explaining the minutiae of Dowland's life, and reading excerpts from the composer's correspondence between songs. This attention to detail enhances the delicate delights of a gossamer ditty such as 'Have You Seen the Bright Lily Grow', written for the soundtrack of a play by Ben Jonson.

''I've played to some of the biggest audiences in history, over half-a-million people at a time,'' says Sting in closing, ''but I've never felt as nervous as I did tonight.'' Such trepidation was unnecessary: against all expectations, this was a genuine tour de force.

(c) The Guardian by Ian Gittins

Unplugged, he's no Renaissance man...

Ever since early music's Pied Piper David Munrow hit the small screen in the Seventies, the lute has steadily moved up the charts as the thinking man's guitar. And Sting is, by -rock standards, the quintessential thinking man: his route to the lute began 20 years ago when a friend propelled him towards Peter Pears and Julian Bream doing John Dowland.

At that time he couldn't see any mileage in it for himself, any more than he could when Katia Labeque suggested that Dowland's songs might suit his ''unschooled tenor'', but he was drawn ever deeper into what he calls the ''labyrinth''. Stuff kept happening: he was given a custom-built lute with a labyrinth-shaped rose-hole, and he stumbled into a collaboration with the Sarajevan lutenist Edin Karamazov.

And, after years of patient readjustment of brain and fingers to this guitar-which-is-not-a-guitar, Sting has now unveiled a CD entitled 'Songs from the Labyrinth', consisting of Dowland's loveliest works interspersed with lute fantasias and extracts from the composer's letters.

Which brings us to the LSO's beautifully converted Hawksmoor church, together with ticket touts, rock celebs, the early-music fraternity and Fiona Talkington, who explains that what we are about to hear will shortly reverberate round every corner of Radios 2 and 3. Taking the stage with Karamazov, Sting modestly remarks that he'll be singing in his own style, ''but one hopes in a respectful way''. And he has a pertinent thought to pass on: Dowland's, he says, is ''the music of self-reflection, which leads.to melancholy, which has nothing to do with depression, and is an undervalued emotion in modern times''. Well put.

Whereupon he launches into 'Flow My Tears'. Having listened to the CD, I've been looking forward to this moment: Sting has none of the preciousness one associates with amateur shots at Dowland, and his mildly transatlantic accent forces me to listen to the music as something entirely new. But what a shock when he opens his mouth: shorn of that studio mastering, which turns recorded dross into gold, his sound is awful, by turns a croon and a rasp. And he's trying so hard, in all the wrong ways, that it positively hurts to listen.

For this church has an unforgivingly faithful acoustic, and Dowland's melodic lines have the beauty of simplicity: Sting is stripped naked. In one pre-concert interview he argued that since this music pre-dated opera, his lack of ''technique'' didn't matter. That may be true, but we're here about something more universal than mere bel canto - about an artistry that spans everything from Big Bill Broonzy to superstar tenor Ian Bostridge, who just happens to be sitting in my row. And poor old Sting, for all his good intentions, simply hasn't got it. It's worst when he attacks one of Dowland's longheld high notes, but it's pretty bad throughout. The only time it becomes bearable is when he roughens up the street-cry in 'Fine Knacks for Ladies', or hardens his tone against his moody mistress in 'Clear or Cloudy'. I begin to long for Bostridge - or any decent folk singer - to replace him, and demonstrate what good singing is.

The concert doesn't last long -just the length of the CD - but when the celebs have given him their ritual ovation he picks up his lute, turns it into a guitar, and launches-into one of his own songs - and we realise that he can sing after all. Performing for 5,000 people is a breeze compared with this, he explains: ''I was never so nervous in my life.'' Now he, his instrument, and his material are one, and we all breathe a collective sigh of relief: don't give up your day job.

(c) The Independent by Michael Church

Sting at LSO St Luke's, EC1...

Ever the Renaissance man, Sting has lately turned his attention to playing the lute, devoting himself for the best part of two years to an intense study of the 16th-century composer and performer John Dowland. The fruits of this “labour of curiosity” can be heard on a new CD, 'Songs from the Labyrinth', a collection of music and readings from the letters of Dowland, performed by Sting and the lutenist Edin Karamazov, which was brought to life at a recital in the restored St Luke’s.

It quickly became clear that Karamazov was going to be shouldering the lion’s share of the actual lute playing. His fingers flew in acrobatic combinations across the giant fretboard, while Sting, sitting bolt upright, broached the dolorous lyric of 'Flow my Tears'. “Let me mourn/ Where night’s black bird her sad infamy sins/ There let me live forlorn,” he sang. The lute sounded glorious - like a classical guitar but fuller and more ripened. And Sting sounded... well, like Sting.

And here was the curious thing. Glib and pretentious as the whole exercise might appear on the surface, there was a clearly discernible link between the millionaire pop star of the 21st century and the wandering minstrel of yore. In technical terms, Sting couldn’t hold a candle to any one of the singers from the vocal group Stile Antico, who joined the duo for a swirling rendition of 'Can She Excuse My Wrongs'. And his lute playing would probably not have earned him a position in the courts of medieval Europe. But the harmonic intervals in Dowland’s airs and the general thrust of a song such as 'The Lowest Trees Have Tops' did not sound that far removed from the music that Sting is known for.

As if to underline the point a mischievous choice of encores included Sting’s own song 'Fields of Gold', a Robert Johnson blues, 'Hellhound on my Trail' and the Police hit 'Message in a Bottle', all rendered in the courtly, lutenist style. Dowland may have been spinning in his grave, but it was surprisingly good fun.

(c) The Times by David Sinclair