Soul Cages

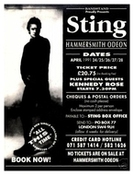

Apr

25

1991

London, GB

Hammersmith Odeonwith Kennedy Rose, Vinx

Protégé parade with real Sting in the tail...

The man they call Sting has ducked more than his fair share of brickbats over the last few years.

First he turned his back on a perfectly good pop group and started making all kinds of portentous sounds, none of which were good for a singalong.

Then he took a long look at all the available evidence regarding pop stars and movies and made a few films anyway.

Finally, he gathered up every homeless, treeless and hopeless thing under his bass playing armpit, and asked us all to care. Too much.

This time round, Sting has cut his baggage and much of the crap, and is presenting a series of straightforward shows with a three piece band.

Cosmic consciousness has adjourned to the bard for the duration. The audience, which ranges from old Police fans to even older Police fans to people who have never heard of the Police, is in place early.

Sting makes his first appearance in the company of two young ladies with the kind of hair that only grows in Texas.

At first, nobody recognises the main in this unaccustomed company, then follows a yelp of joy.

But he is only there to introduce the first of his protégés for the evening, Kennedy Rose, a duo from somewhere like Texas.

They keen away harmlessly, albeit rather earnestly, but trouble arrives when one takes to a tiny drum kit and starts making a racket like a drunk in a broom cupboard.

Sting reappears with another protégé. This one is a large black man with blur hair and an enormous drum. He is called Vinx, has a wonderful voice, some smart lyrics and the enviable ability to engage normal looking people in obscene singalongs.

Sting makes his third appearance of the evening, seemingly unaffected by all this walking and this time stays put. You can tell it is no-nonsense time by the way his black pants are hoicked high by a pair of braces that could double as extra bass strings. He is in a merry mood, sprinkling his conversation with what can only be called f-words. Instead of the expected green, the air suddenly turns blue.

Sting is in fact, a very fine bass player even if he does look a bit like Jeffrey Archer. He is ably supported by a young guitarist with a beautifully distant tone, and a keyboard player who conjures up extraordinary noises by means of a baby pacifier.

The drummer loudly spanks any signs if inattention. After a nifty version of 'Ain't No Sunshine', Sting asks for any requests and promptly cranks out the expected 'Roxanne' without a qualm.

Three cheers for Gordon.

(c) The Mail On Sunday by Pete Clark

Bass pleasures...

The pre-show entertainment on the bar television was Australian Rugby League. It was about as appropriate for this crowd as the All-England Badminton finals before AC/DC.

In the Gents, two fans were discussing a recent film about American design they had seen on The Late Show. Sting, along with Elvis Costello, is alone among the generation of performers who emerged in the late Seventies in having taken his audience with him as he has grown.

First he played spiky student reggae-pop, then he moved up to clever rock with lyrics about mass murder and nuclear power.

Then he went solo, got committed, turned green, went jazzy, cooled out and now looks rather shambolic. Bit like all of us, really.

It is 12 years since he played the Hammersmith Odeon and he asked his polite audience (so polite the chap next to me jumped out of his skin at a drum report during 'Why Should I Cry?') how many had been there in 1979. ''I was,'' someone yelled. ''And how old are you, Sir?'' asked Sting politely, rising to the prevalent mood. ''14,'' came the reply, which threw our man completely.

In a recent interview for this paper, Sting said that some of the reviews for 'The Soul Cages', his latest album, were so vicious they constituted hate mail. As one whose opinion on the record perhaps would have been better expressed in letters torn from a newspaper, I had no great expectations of this gig. It came, then, as a very pleasant surprise.

Gone was the over-indulgent flab of his last performances in Britain, in big stadiums with purple light shows and sophisticated suits. Here he concentrated on the musicianship, bringing with him Branford Marsalis on sax, David Sancious on keyboards, Dominic Miller on guitar, Vinnie Colaiuta on drums and his own not inconsiderable talent on bass. With a backing band that tasty, no wonder there was no money left over for a light show (apart from some quaint, acid-style liquid slides projected on to the back-cloth during a storming cover of 'Purple Haze'.)

And with a backing band that tasty, whatever Sting decided to do sounded the business. He gave us a good selection from each stage of his career, with a little too much of the recent obsession with the sea.

In the oceanic mid-point of the evening the jazz-club feel of the Odeon was completed as couples nodded off on each other's shoulders in the heat, and people chatted loudly at the back. But this was the only doubtful 10 minutes in over two hours.

Sting has written a good number of songs to be proud of, 'When the World is Running Down', 'King of Pain' and 'Walking on the Moon', for instance, and they can never have been played better than here. The encore, 'Fragile' (from the '...Nothing like the Sun' album), with him on acoustic guitar and everyone else shaking oddments of percussion, was almost up there with that trio.

And he made a mock fuss - ''Any requests? Why does everyone always ask for that?'' - but he even played 'Roxanne'. It was, needless to say, memorable. I almost rushed out to buy the new album.

(c) The Independent by Jim White

Sting harks back...

Sting's residency at Hammersmith Odeon this week is the latest stop on a tour across two continents to promote his new album, 'The Soul Cages'.

That in itself is a bit of a surprise, for so much of his travelling recently has been concerned with much more universal issues. Sting deep in the Amazon basin befriending the Amerindians might have been a publicity stunt, but the images from the Amnesty tour, of Sting singing 'They Dance Alone' in the Santiago football stadium with the mothers of the disappeared, were much harder to dismiss as self-promotion.

Yet as the album suggests and the concert on Thursday confirmed, his concerns are currently much closer to home - not a mention of human rights or saving the rainforests, and instead a distinct emphasis upon the brand-new songs which evoke his Tyneside childhood, right alongside material dating back to his Police beginnings.

No Sting appearance would be complete, I suppose, without 'Roxanne' and 'Message in a Bottle', but even so it was curious to find a singer who has developed and so intricately expanded his song writing harking back with such insistence - he also included 'King of Pain', and the wonderfully obsessive 'Every Breath You Take' from the early 1980s - while making only token selections from each of his first two solo albums, one of those, 'Fragile', as a beautifully poised encore.

And just what were we to make of his moderately wild version of 'Purple Haze', complete with convincing ersatz Hendrix guitar from Dominic Miller, or of Bill Withers' 'Ain't no Sunshine'? The roots he's after at the moment seem to be as much musical as nostalgic.

It matters only because Sting is one of the most prodigiously talented of current rock musicians, a vocalist of significant range and technical skill and a songwriter of increasing sophistication, whose previous albums worried away at the edges of jazz and rock and several kinds of fusion.

The band for the current tour still includes the jazz saxophonist Branford Marsalis, but his limpid playing is now buried much more deeply in the arrangements. There is none of the dueting of voice and sax that carried so much charge in the last two albums and instead the keyboards of David Sancious (of Springsteen's E-Street Band) are more prominent, and the looser moments now hard-edged rather than poetic.

The tracks from 'The Soul Cages' are all concerned with going back, with recovering childhood memories, especially of the sea, and repaying familial debts. They're more intricately structured than before, less instantly accessible, though the modulations are as telling as ever, the melodic lines insidiously memorable.

Yet Sting appears to be torn between the need to indulge the adulation of his fans and the compulsion to explore the limits of his own music; somebody who can write songs as fine as 'Mad About You' and 'The Wild Wild Sea' in the new collection really does not need to manipulate an audience like he does simply to convince himself that they still love him so much.

(c) The Financial Times by Andrew Clements

The man they call Sting has ducked more than his fair share of brickbats over the last few years.

First he turned his back on a perfectly good pop group and started making all kinds of portentous sounds, none of which were good for a singalong.

Then he took a long look at all the available evidence regarding pop stars and movies and made a few films anyway.

Finally, he gathered up every homeless, treeless and hopeless thing under his bass playing armpit, and asked us all to care. Too much.

This time round, Sting has cut his baggage and much of the crap, and is presenting a series of straightforward shows with a three piece band.

Cosmic consciousness has adjourned to the bard for the duration. The audience, which ranges from old Police fans to even older Police fans to people who have never heard of the Police, is in place early.

Sting makes his first appearance in the company of two young ladies with the kind of hair that only grows in Texas.

At first, nobody recognises the main in this unaccustomed company, then follows a yelp of joy.

But he is only there to introduce the first of his protégés for the evening, Kennedy Rose, a duo from somewhere like Texas.

They keen away harmlessly, albeit rather earnestly, but trouble arrives when one takes to a tiny drum kit and starts making a racket like a drunk in a broom cupboard.

Sting reappears with another protégé. This one is a large black man with blur hair and an enormous drum. He is called Vinx, has a wonderful voice, some smart lyrics and the enviable ability to engage normal looking people in obscene singalongs.

Sting makes his third appearance of the evening, seemingly unaffected by all this walking and this time stays put. You can tell it is no-nonsense time by the way his black pants are hoicked high by a pair of braces that could double as extra bass strings. He is in a merry mood, sprinkling his conversation with what can only be called f-words. Instead of the expected green, the air suddenly turns blue.

Sting is in fact, a very fine bass player even if he does look a bit like Jeffrey Archer. He is ably supported by a young guitarist with a beautifully distant tone, and a keyboard player who conjures up extraordinary noises by means of a baby pacifier.

The drummer loudly spanks any signs if inattention. After a nifty version of 'Ain't No Sunshine', Sting asks for any requests and promptly cranks out the expected 'Roxanne' without a qualm.

Three cheers for Gordon.

(c) The Mail On Sunday by Pete Clark

Bass pleasures...

The pre-show entertainment on the bar television was Australian Rugby League. It was about as appropriate for this crowd as the All-England Badminton finals before AC/DC.

In the Gents, two fans were discussing a recent film about American design they had seen on The Late Show. Sting, along with Elvis Costello, is alone among the generation of performers who emerged in the late Seventies in having taken his audience with him as he has grown.

First he played spiky student reggae-pop, then he moved up to clever rock with lyrics about mass murder and nuclear power.

Then he went solo, got committed, turned green, went jazzy, cooled out and now looks rather shambolic. Bit like all of us, really.

It is 12 years since he played the Hammersmith Odeon and he asked his polite audience (so polite the chap next to me jumped out of his skin at a drum report during 'Why Should I Cry?') how many had been there in 1979. ''I was,'' someone yelled. ''And how old are you, Sir?'' asked Sting politely, rising to the prevalent mood. ''14,'' came the reply, which threw our man completely.

In a recent interview for this paper, Sting said that some of the reviews for 'The Soul Cages', his latest album, were so vicious they constituted hate mail. As one whose opinion on the record perhaps would have been better expressed in letters torn from a newspaper, I had no great expectations of this gig. It came, then, as a very pleasant surprise.

Gone was the over-indulgent flab of his last performances in Britain, in big stadiums with purple light shows and sophisticated suits. Here he concentrated on the musicianship, bringing with him Branford Marsalis on sax, David Sancious on keyboards, Dominic Miller on guitar, Vinnie Colaiuta on drums and his own not inconsiderable talent on bass. With a backing band that tasty, no wonder there was no money left over for a light show (apart from some quaint, acid-style liquid slides projected on to the back-cloth during a storming cover of 'Purple Haze'.)

And with a backing band that tasty, whatever Sting decided to do sounded the business. He gave us a good selection from each stage of his career, with a little too much of the recent obsession with the sea.

In the oceanic mid-point of the evening the jazz-club feel of the Odeon was completed as couples nodded off on each other's shoulders in the heat, and people chatted loudly at the back. But this was the only doubtful 10 minutes in over two hours.

Sting has written a good number of songs to be proud of, 'When the World is Running Down', 'King of Pain' and 'Walking on the Moon', for instance, and they can never have been played better than here. The encore, 'Fragile' (from the '...Nothing like the Sun' album), with him on acoustic guitar and everyone else shaking oddments of percussion, was almost up there with that trio.

And he made a mock fuss - ''Any requests? Why does everyone always ask for that?'' - but he even played 'Roxanne'. It was, needless to say, memorable. I almost rushed out to buy the new album.

(c) The Independent by Jim White

Sting harks back...

Sting's residency at Hammersmith Odeon this week is the latest stop on a tour across two continents to promote his new album, 'The Soul Cages'.

That in itself is a bit of a surprise, for so much of his travelling recently has been concerned with much more universal issues. Sting deep in the Amazon basin befriending the Amerindians might have been a publicity stunt, but the images from the Amnesty tour, of Sting singing 'They Dance Alone' in the Santiago football stadium with the mothers of the disappeared, were much harder to dismiss as self-promotion.

Yet as the album suggests and the concert on Thursday confirmed, his concerns are currently much closer to home - not a mention of human rights or saving the rainforests, and instead a distinct emphasis upon the brand-new songs which evoke his Tyneside childhood, right alongside material dating back to his Police beginnings.

No Sting appearance would be complete, I suppose, without 'Roxanne' and 'Message in a Bottle', but even so it was curious to find a singer who has developed and so intricately expanded his song writing harking back with such insistence - he also included 'King of Pain', and the wonderfully obsessive 'Every Breath You Take' from the early 1980s - while making only token selections from each of his first two solo albums, one of those, 'Fragile', as a beautifully poised encore.

And just what were we to make of his moderately wild version of 'Purple Haze', complete with convincing ersatz Hendrix guitar from Dominic Miller, or of Bill Withers' 'Ain't no Sunshine'? The roots he's after at the moment seem to be as much musical as nostalgic.

It matters only because Sting is one of the most prodigiously talented of current rock musicians, a vocalist of significant range and technical skill and a songwriter of increasing sophistication, whose previous albums worried away at the edges of jazz and rock and several kinds of fusion.

The band for the current tour still includes the jazz saxophonist Branford Marsalis, but his limpid playing is now buried much more deeply in the arrangements. There is none of the dueting of voice and sax that carried so much charge in the last two albums and instead the keyboards of David Sancious (of Springsteen's E-Street Band) are more prominent, and the looser moments now hard-edged rather than poetic.

The tracks from 'The Soul Cages' are all concerned with going back, with recovering childhood memories, especially of the sea, and repaying familial debts. They're more intricately structured than before, less instantly accessible, though the modulations are as telling as ever, the melodic lines insidiously memorable.

Yet Sting appears to be torn between the need to indulge the adulation of his fans and the compulsion to explore the limits of his own music; somebody who can write songs as fine as 'Mad About You' and 'The Wild Wild Sea' in the new collection really does not need to manipulate an audience like he does simply to convince himself that they still love him so much.

(c) The Financial Times by Andrew Clements